Lessons I learned from failing as an entrepreneur

I am a failed entrepreneur.

People protest when I say this, so let me explain what I mean by it: I started a business, it was hard, several years later I pursued an exit, the deal fell through at the last minute, and since I had by then already accepted a job offer, I made the tough call to shut the company down.

Here’s the story: I founded a company called Plasta, and created a range of plasters (band-aids) for different skin tones. I launched a total of twelve SKUs, with four products each available in three tones. Plasta was on shelf in over 200 stores in Southern Africa and the Netherlands (looking back, this feels somewhat serendipitous since I live here now). The company garnered some truly exciting international media attention including a feature on CNN, The Daily Mail, and Yahoo News, and being on the front page of The Daily Voice - I took down one of the lamppost headline placards and had it framed; it is hanging in my kitchen in Amsterdam today:

Of course I know that I shouldn’t refer to this venture as failure, and I know that taking on the challenges of entrepreneurship is no mean feat, regardless of the outcome. But I also can’t boast about selling my company, getting it to hundreds of millions in revenue, or being on any of the numerous “X under X” lists applauding people’s achievements.

And that’s okay.

It took me a long time to come to terms with this “failure” (I’ve explained what I mean by this so let’s just call it that for the sake of brevity). But at some stage I took stock of what I gained, even in the losses. And now I say it with my chest: I am a failed entrepreneur! In fact, in job interviews and any other career-related discussions, I lead with it. This felt risky at first but I quickly realised that it is the right approach. Entrepreneurship is hard. There aren’t enough words in the dictionary for just how hard it is. I maintain that what I learnt in my time as an entrepreneur contributed more than anything else towards my being accepted at INSEAD, getting a job in Accenture’s M&A team, in McKinsey’s Private Equity & Principal Investors practice, and most recently at a private equity firm.

This being a consumer industry x investment newsletter, and my having founded a consumer packaged goods company, this week’s edition is dedicated to the biggest lessons, both personal and professional, I learnt from failing at entrepreneurship:

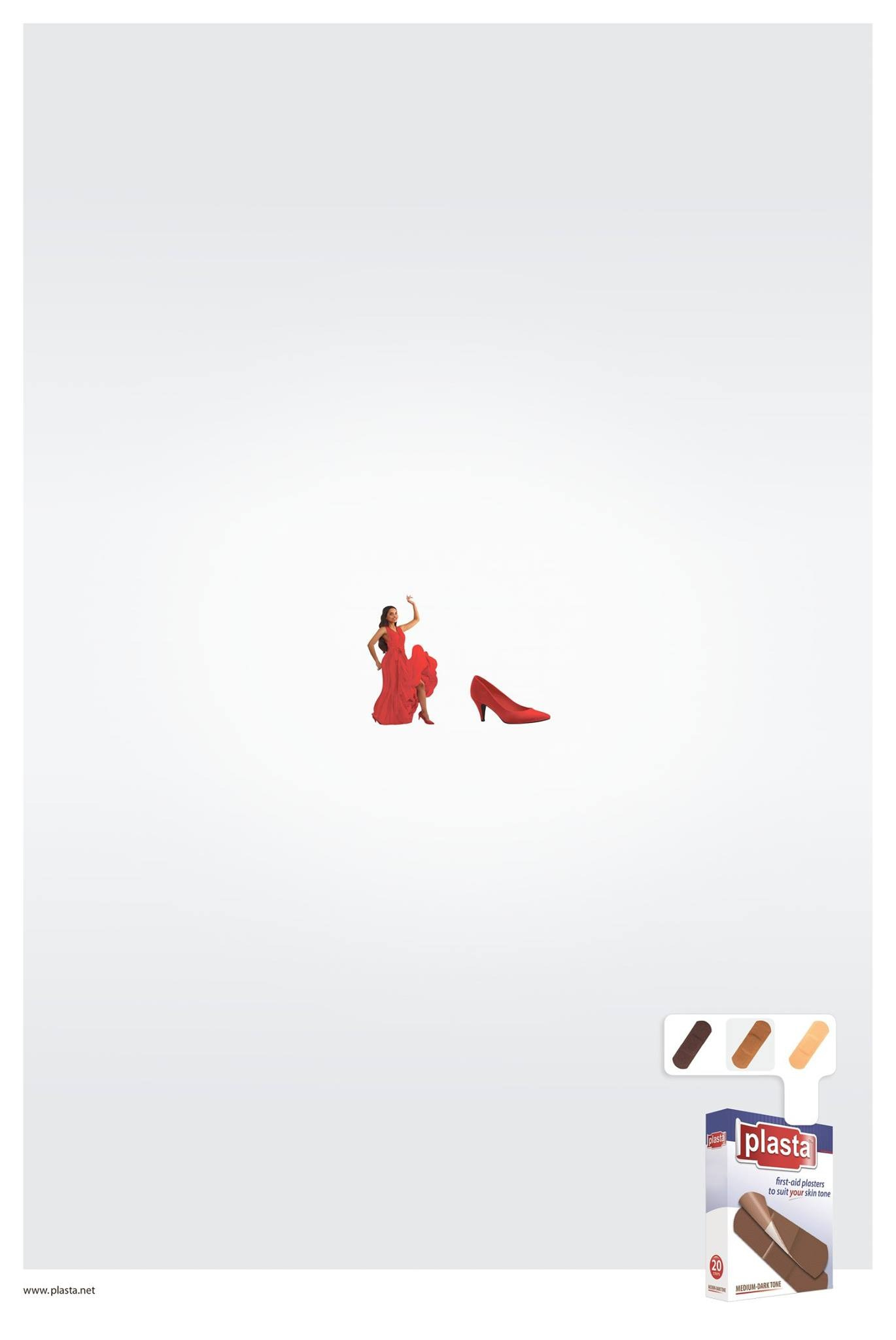

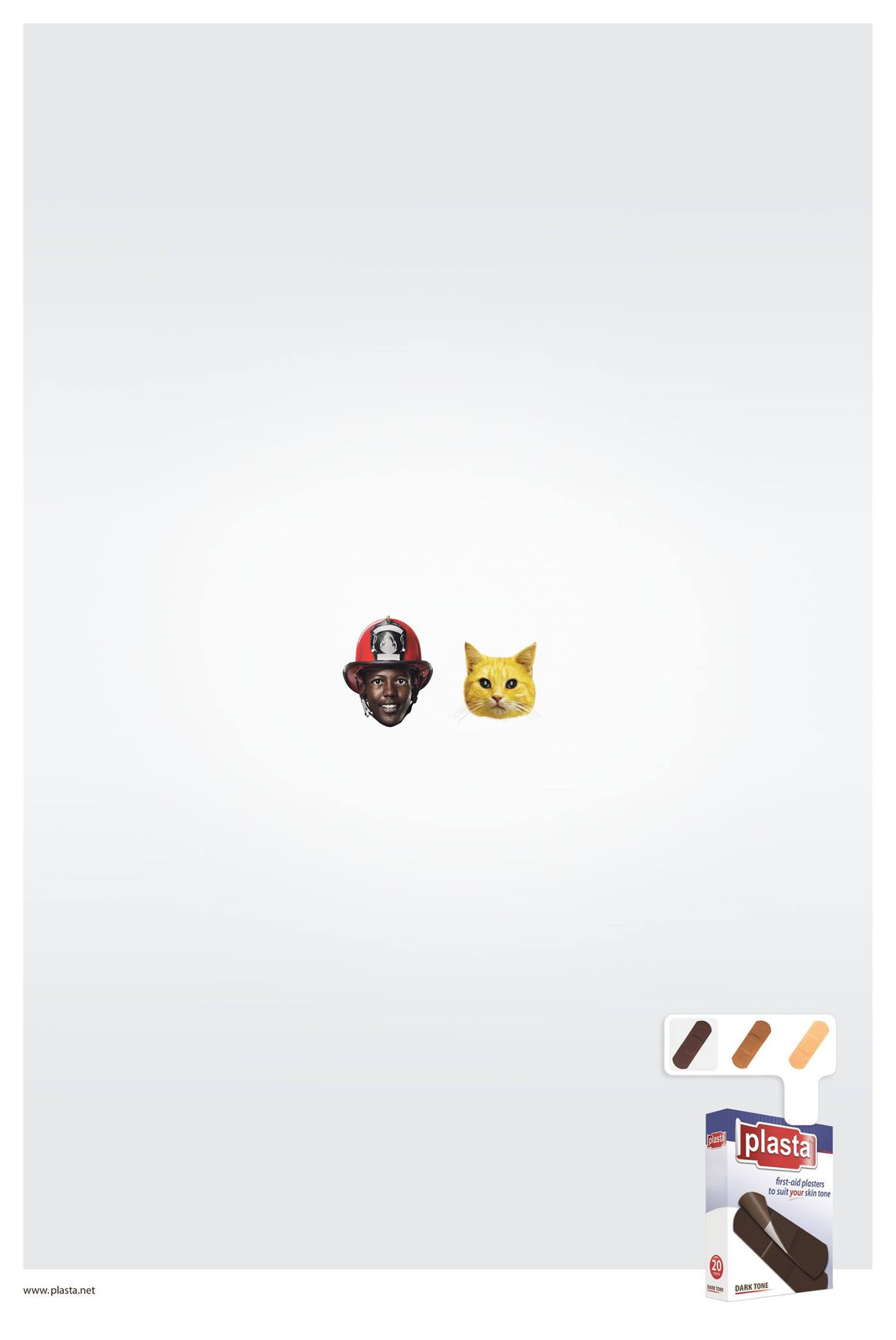

The importance of marketing: This probably sounds really obvious but as someone who didn’t come from a marketing background, I underestimated its importance hugely. I was aware that I would need to market the product, but since I bootstrapped the business the budget I could allocate to marketing was tiny. I tried to be as strategic as possible, focusing on channels that were affordable (social media, for example). M&C Saatchi Abel approached me to create a campaign for the brand - since it was a first-to-market product, there were opportunities to get really creative and potentially nab an award - and I loved what they came up with (this was around the time where emojis were for the first time offering more diverse options - including different skin tones - and the timing was perfect). But what I realise now is that this, being both a new concept and a new brand, needed an extensive, through-the-line campaign. I needed customers to have seen and/or heard the brand name and product multiple (and I mean, multiple!) times before seeing the product on the shelf if I had any hope of them actually buying it.

What would I do differently today? I would get funding and put a substantial portion of it towards a great TTL marketing campaign.

The chicken/egg conundrum of marketing and distribution: When I landed my first big retailer part of the contract terms required that I pay for marketing through their channels for a period of time before they would put the product on shelf. This struck me as a cart-before-the-horse approach, and the way in which I negotiated for distribution and marketing to happen simultaneously was with a personal anecdote: A few months prior while I was travelling in Latvia, I saw advertising everywhere for one of my favourite ice creams as a child, which had been discontinued many years prior and was ostensibly back. I was so excited, and made it my mission to eat as many of them as I could before heading home. To say I went into every single grocery store, corner store, café, deli, and ice cream truck I saw is no exaggeration. And yet, the ice creams were not yet in stock in any of them. It was frustrating to me as a consumer (and heartbreaking for that excited ten-year-old version of me), and it taught me a big lesson in the consumer business. The retailer agreed, and I avoided wasting marketing spend on a product that could not, at that stage, be bought.

What would I do differently today? Nothing. I still believe that distribution without marketing will lack impact, but the inverse is utterly illogical.

The scale imperative: Challenger brands often see exciting levels of early momentum but reach a point where they can no longer build on that. In my particular case, this was a business with decent margins, but low value per sale. Long-term financial feasibility in this scenario requires serious scale. In the case of consumer packaged goods, this is particularly difficult to achieve outside of a robust existing CPG infrastructure (e.g., being part of a conglomerate such as Unilever or Beiersdorf) for various reasons, key among them being retailer relationships and distribution networks (in the beginning stages where getting on shelf was vital I had multiple cases of shipping eating up all of my profits which is not sustainable long-term).

What would I do differently today? Get a strategic co-founder or advisor with relevant professional experience on board, to leverage their industry expertise and connections. I advise people to be cautious when giving up equity because it’s easy to give away and nigh on impossible to get back, but in this case I think an equity stake in exchange for knowledge would have been a strategic move.

First-to-market is hard. The problem with a first-to-market product, as mine was, is that there is often a lot of hype around it and it is easy to get a bit carried away by that. But there is a string of early movers that came before the most successful players in various industries today. Think of Vine vs TikTok, MySpace vs Facebook, Napster vs Spotify, and BlackBerry vs iPhone. Pioneers often do a lot of the heavy lifting around consumer perception and market buy-in, but the very challenges of being the first can be enough to bring everything to a halt - all while leaving behind a far more navigable path for those that follow.

What would I do differently today? I would do… better. There is no sense in waiting for someone else to do something first, purely for the sake of being able to follow. I would still take the risk of being a first mover, but implement all of the lessons I am listing here for the best chance of making a success of it despite the challenges inherent in leading the way.

Take stock of your strengths and shortcomings: Entrepreneurship is rarely a clearly-defined job. Especially if you are bootstrapping a business like I did, at some point or another you will have to step into pretty much every function in the business, like it or not. This is a great time to take note of what you are good at, less good (or even really bad) at, what you enjoy and find interesting, and what feels like pulling teeth. These realisations are important in informing your long-term career decisions, and finding the best formula possible to make your venture a success. If you can be honest about your shortcomings, and humble enough to plug the gaps by surrounding yourself with brilliant people who have complementary skillsets, you’ll have a greater chance of succeeding than if you try to do- and be everything yourself.

What would I do differently today? Similarly to the learning in point 3, I would build a team (which would require, as per the learning in point 1, funding) rather than trying to do it all myself.

More of a slog than a hustle: Entrepreneurship is perceived as exciting and interesting and glamorous, when it fact the majority of the work is tedious and uninspiring. You will take out the trash, battle with mundane and inefficient bureaucratic nonsense that seems utterly ridiculous yet prevents you entirely from doing business, and deal with more rejection than in all your school years combined. You will be broke, stressed, and exhausted. Your relationships and health will probably suffer, and the rollercoaster of emotions will age you out of any retinol serum’s ability to pump the brakes on those stress lines forming. People think entrepreneurship is all hustle, when it fact it’s mostly a slog. Many people take on entrepreneurship chasing and motivated by the hustle (late-night brainstorming, investor pitches, press coverage), while being thoroughly unprepared for- and disinterested in the inevitable slog. Motivation runs out, and when it does, discipline needs to kick in. If you don’t have discipline, resilience, and grit, stick to corporate.

What would I do differently today? Nothing. I’m a workhorse (and a show pony - #getyourselfagirlwhocandoboth) and the periods of slogging did not put me off or slow me down. Perhaps I’d give myself a stern pep talk if ever I wanted to revisit entrepreneurship, though, just to make completely sure I’m up for round two.

Chase the right thing. There’s nothing wrong with selling your company - a lucrative exit is many entrepreneurs’ dream, and as explained in point 3, a lot of companies hit a ceiling that is hard to break through without a big boost in funding and capabilities, which often comes in the form of acquisition. But not every startup gets there, and even if yours does, there will likely be countless unexpected setbacks and hurdles along the way. I urge all entrepreneurs to truly believe in what they are creating, the problem they are solving. Money is nice, and it is motivating, but I believe that having a greater mission as your north star is what will guide you and keep you going despite the challenges along the way.

What would I do differently today? You guessed it - nothing. In hard times, including failing to achieve that ambitious final goal, what kept me driven was the impact of the product I had created. I received countless emails and social media messages from strangers all around the world thanking me for creating it. To have contributed towards feelings of inclusion, driven a conversation that heightened awareness around important topics, and given people the feeling of being seen in a small, specific, but important way for the first time - that made it all worth it. I would take on every single one of the challenges of that journey again, failure included, for the purpose of getting that product out in the world and into people’s lives.

Entrepreneurship has enriched me (not financially, mind!) in so many ways. I learnt so much about myself, and about business, and emerged from it equipped with a host of truly invaluable skills (in life and in work) and a strengthened character and sense of self. Failing will without a doubt make me a better entrepreneur in the future, should I pursue my own venture again. It has also made me a better investor, a better mentor, and better at my job.

The saying “nothing ventured, nothing gained” could not be more applicable than in the case of entrepreneurship. Notwithstanding the lack of financial fortune that flowed from this endeavour, I am infinitely richer for it.