Does the world really need another celebrity beauty brand?

Martha Stewart is the latest celebrity to launch a skincare range, and the category is nearing saturation. Investors should approach with caution, and not only because of consumer fatigue.

There is currently no shortage of celebrity beauty brands in the world. I’ve previously written about e.l.f’s acquisition of Hailey Bieber’s brand rhode, but there’s also Kylie Jenner’s Kylie Cosmetics, Rihanna’s Fenty, Selena Gomez’s Rare Beauty, Lady Gaga’s Haus Labs - the list goes on (and on, and on). Mention of celebrity beauty brands will usually invoke names of female celebrities and the brands associated with them, while male celebs might be more readily associated with alcohol brands* - Ryan Reynolds’ Aviation Gin, George’s Clooney’s Casamigos tequila, and Dr Dre and Snoop Dogg’s Gin & Juice. But the proliferation of male celebrity-owned skincare and cosmetics brands cannot be ignored: John Legend’s Loved01, Harry Styles’ Pleasing, and Pharrell Williams’ Humanrace (which I could almost be convinced by, based purely on how remarkably well he has aged).

Martha Stewart is the latest to launch a skincare line (partnering with the dermatologist behind rhode, Dr Dhaval Bhanusali), but the celebrand currently generating buzz is Brad Pitt’s skincare line Beau Domaine. Using ingredients from wine grapes in its formulations, the recently rebranded line has attracted the ire of the beauty community to the extent that a website was created to host an open letter to the founder, essentially begging him to stay in his lane.

In a way the proliferation of celebrity cosmetics brands isn’t entirely new. At the turn of the century every second celebrity seemed to have a fragrance, from Britney Spears to Antonio Banderas, but somehow with skincare it feels different. This is because skincare promises something more - results, science, efficacy. It also requires more, in the form of expertise, quality ingredients, and, ideally, clinical trials. For a celebrity to slap their name onto a fragrance therefore feels less inauthentic than when they do the same thing on a product category that is (or at least, should be) about much more than pretty packaging and a catchy name - and that is what is driving fatigue around celebrity beauty- and skincare brands.

But what about celebrity brands as an investment theme? Several have seen news-worthy investment activity including e.l.f’s acquisition of rhode, Coty’s majority stake in Kylie Cosmetics, and Honest Company’s listing on the NASDAQ. But for every success story there are brands flailing despite the star power behind them. Investing in celebrity brands poses unique risks which should be front and centre in any due diligence processes and findings:

Over-reliance on founders: Finding the sweet spot between leveraging a celebrity founder’s reach and relying entirely on their persona is a fine balancing act. There are brands that get it right: Rare, rhode, and Fenty come to mind (Bobbi Brown and Charlotte Tilbury can be used as examples of brands not being overly-reliant on their namesakes, though these are perhaps not the best comparisons as the founders aren’t celebrities in the same way Beyoncé is a celebrity). In these examples the founder’s status is a boost but, importantly, the products speak for themselves. Others need to lean heavily on the founder’s name from the start: Kylie Cosmetics is a good example of a brand deeply entangled in the founder’s persona (though that is arguably by design). But in the saturated beauty space brands such as Rosie Hunting-Whiteley’s Rosie Inc. and Jonathan Van Ness’s JVN would not exist without carrying their names. The problem arises when those founders step away, for example RHW no longer being involved with Rosie Inc. after incubator Amyris filed for bankruptcy and sold the brand to AA Investments, cutting the founder out entirely. Authenticity (which is already lacking in many celebrity brands) plummets and interest dwindles as the drawcard for many consumers is removed.

Headline risk: What is harder to forecast than future revenues? Celebrity behaviour. There is no shortage of examples of celebrities putting their foot in it, be it due to being caught behaving poorly, saying something inflammatory on social media, or involvement in more sinister scandals. Plenty of brands have been burned after partnering with celebrities who later do serious damage simply by virtue of who they are (adidas x Kanye comes to mind, though I’d argue that one wasn’t so difficult to predict). Unlike Hello Kitty and Mickey Mouse, human celebrities are all too real. That comes with considerable headline risk, and there’s no escaping the fact that in the case of celebrity brands, reputation damage is brand damage.

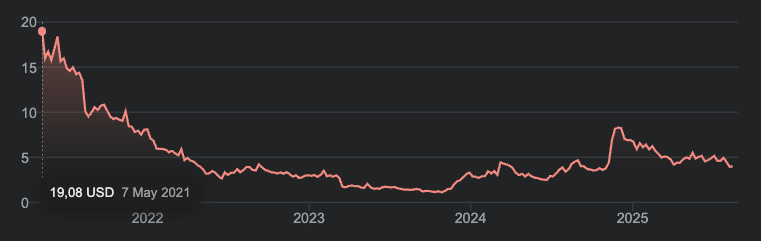

Volatile hype cycle: The celebrity factor means many of these brands see an initial boost due to a huge amount of hype at launch. When a founder has far-reaching influence including millions (if not tens- or even hundreds of millions) of social media followers, this part is easy. The real challenge lies in sustaining interest over time. Authenticity and products that truly perform (plus ongoing innovation, a must in beauty) are key. But that initial period of hype often makes for frothy valuations, with multiples inflated by social media buzz rather than proven, sustainable EBITDA. Early-stage overinflated valuations will almost always lead to value destruction down the line, so it’s important to try separate novelty from the realistic long-term outlook of the brand.

Scaling limitations: There are celebrities who are universally adored (or at least acknowledged), while others’ relevance is more geographically limited. Investment in a consumer brand will almost always come with the intention to expand and scale, and if a famous founder does not resonate in a large market, that opportunity may be dead in the water. This goes against the core investment thesis of most private equity firms and strategic buyers, and should (but does not always, because diligence is hard and finance FOMO is real) preclude them from making these acquisitions.

Identity tethers: This overlaps partly with point 1, but has a longer-term lens. If a brand is making a success of leaning on founder status, it also means that brand value is tied to it. A famous founder stepping away, whether by force or not, will impact the brand. And post-exit, the person will still carry their name, meaning brand IP is never owned or controlled in quite the same way as brands that don’t include founders’ names. Bobbi Brown is still out there (and launched Jones Road beauty the day the non-compete clause, put in place when Estée Lauder Companies acquired her brand, expired). She is using her name because, outside of a world-famous makeup brand, it is also just that - her name. The flip side of this is that celebrity founder priorities may not align with investor objectives, and decision-making becomes even more contentious than it is in ordinary boardrooms. It is yet another delicate balancing act, and the solution will look different for every one of the seemingly countless celebrity brands out there.

If I had to make a sweeping generalisation, I’d advise steering clear of investing in celebrity brands. Few have proven themselves to be sustainable in the long term, and the risks are high and hard to predict.

Due diligence in M&A is hard enough; diva diligence is a different thing entirely.

*To be clear, we also definitely, categorically, and absolutely do not need another celebrity alcohol brand.